Historical Stages of the Bank of China (BOC)

The history of the Bank of China (BOC) is a reflection of China’s modern financial and political evolution. It has transformed from a government-run central bank into a leading international commercial bank.

1. Founding and Early Years (1912–1928)

Following the Xinhai Revolution, the Bank of China was established in January 1912 in Shanghai, replacing the Ta-Ching Government Bank.

- 1912: Authorized by Sun Yat-sen, it began operations on February 5, initially serving as the central bank of the Republic of China.

- Responsibilities: It managed the national treasury, issued banknotes, and handled government debt.

- Early Globalization: In 1917, it opened its first overseas office in London, marking the beginning of Chinese banking in the international market.

Core Policy: State Bank Mandate. Authorized by the Nanjing Provisional Government, the BOC functioned as the de facto central bank. Its primary policy goals were to unify the currency system, issue government bonds, and manage the national treasury.

Revenue Level: Official consolidated data from this era is fragmented. However, revenue was primarily driven by seigniorage (banknote issuance) and interest from government financing. As the most internationalized Chinese bank, its London office (est. 1917) began contributing early foreign exchange service fees.

2. Transition to an International Exchange Bank (1928–1949)

With the establishment of the Central Bank of China by the Nanjing government, BOC’s role shifted toward specialized finance.

- 1928: It was designated as a government-chartered international exchange specialist bank.

- Core Business: It focused on foreign exchange, overseas Chinese remittances, and financing international trade.

- War Period: During the Second Sino-Japanese War, it relocated inland to support the national economy and manage war-time financial supplies.

Core Policy: International Exchange Specialization. After the Central Bank of China was established, the BOC was repositioned by the Nanjing government. Policy focused on supporting foreign trade and managing overseas Chinese remittances.

Revenue Level: Revenue shifted toward foreign exchange commissions and international settlement fees. Despite the volatility of the war period, the BOC maintained its status as a financial pillar by leveraging its monopoly on trade-related financial services.

3. Transformation under the People’s Republic (1949–1978)

After 1949, the bank was taken over by the new government and integrated into the planned economy.

- Specialized Role: It became the state’s specialized foreign exchange bank, managed by the People’s Bank of China.

- International Link: During China’s period of relative economic isolation, BOC served as the primary window for the country’s limited economic interactions with the West.

Core Policy: Centralized FX Management. Under the PRC system, the BOC became the sole designated foreign exchange bank. Its policy mandate was strictly to execute the state’s foreign exchange income and expenditure plans rather than pursue commercial profit.

Revenue Level: Financial performance was not measured by commercial standards; profits were essentially the surplus of the state’s trade activities. Revenue depended entirely on national import/export volumes, with all “profits” remitted to the state treasury.

4. Reform and Modernization (1979–2004)

As China launched its “Reform and Opening-up” policy, BOC transitioned toward becoming a commercial entity.

- 1979: The State Council granted BOC independence from the People’s Bank of China, reporting directly to the State Council.

- 1994: Following banking reforms, it transitioned into a state-owned commercial bank.

- Hong Kong Issuance: In 1994, BOC became an official banknote issuer in Hong Kong.

Core Policy: Market-Oriented Commercialization. Starting in 1979, the BOC gained independence from the People’s Bank of China. By 1994, it transitioned into a state-owned commercial bank with the policy goal of establishing a modern corporate governance structure and addressing historical Non-Performing Loans (NPLs).

Revenue Level: Revenue grew exponentially alongside China’s trade boom. Net Interest Margin (NIM) began to replace exchange fees as the primary revenue driver. However, net profit was often suppressed by the need to write off large amounts of bad debt during the structural reforms of the late 1990s.

5. Joint-Stock Reform and Global Expansion (2004–Present)

This era marks BOC’s entry into the modern global financial system with a focus on corporate governance and transparency.

- 2004: Bank of China Limited was officially incorporated as a joint-stock commercial bank.

- 2006: It successfully listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange (H-shares) and the Shanghai Stock Exchange (A-shares), becoming the first Chinese bank to list in both markets.

- Current Status: Today, BOC is China’s most internationalized bank, operating in over 60 countries and regions. It is consistently ranked as a Global Systemically Important Bank (G-SIB).

Core Policy: Capital Market Integration & G-SIB Compliance. Since its IPO in 2006, policy has focused on market-driven operations and global transparency. As a Global Systemically Important Bank (G-SIB), it must adhere to strict international capital adequacy and risk management standards.

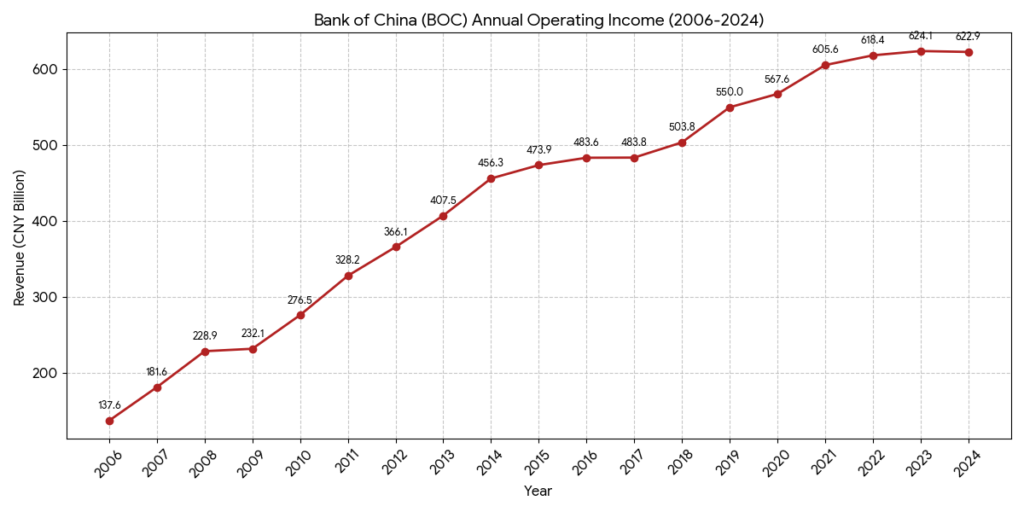

Revenue Level: Entered the “Trillion RMB” era.

- 2024–2025: Annual revenue stabilized around 140 billion USD (approx. 1 trillion RMB).

- Recent Trends (2025-2026): While NIM has faced downward pressure due to domestic interest rate cuts, the bank’s non-interest income (fees and global operations) remains a strong buffer, contributing nearly 30% of total profit.

Competitive Analysis of Bank of China (BOC)

The competitive landscape for the Bank of China is defined by its position within the “Big Four” state-owned banks in China and its unique role as the country’s most internationalized financial institution.

1. Peer Comparison: The “Big Four” (2025–2026 Estimates)

BOC competes directly with Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), China Construction Bank (CCB), and Agricultural Bank of China (ABC).

| Metric (2025 Est.) | ICBC | CCB | ABC | BOC |

| Core Strength | Largest Assets | Infrastructure & Mortgages | Rural & County Coverage | Cross-border & Overseas |

| Total Assets | 1st (45T+ RMB) | 2nd | 3rd | 4th (~33T+ RMB) |

| Net Interest Margin (NIM) | ~1.61% | ~1.70% | ~1.60% | ~1.59% (Lowest) |

| NPL Ratio (Risk) | ~1.33% | ~1.35% | ~1.32% | 1.26% (Best Quality) |

| Overseas Revenue % | Low | Low | Very Low | Highest (~25%) |

2. SWOT Analysis

Strengths

- Leading Globalization: With a presence in over 60 countries, BOC is the primary channel for RMB cross-border settlement and clearing.

- Superior Asset Quality: BOC consistently maintains the lowest Non-Performing Loan (NPL) ratio among the Big Four, indicating a more conservative and robust risk management framework.

- Dual-Listing & BOC Hong Kong: Its strong foothold in Hong Kong as a note-issuing bank provides a unique gateway to international capital markets.

Weaknesses

- Smaller Domestic Footprint: Compared to ABC (rural) or CCB (urban communities), BOC has fewer domestic branches, resulting in lower retail penetration in mainland China.

- Interest Rate Sensitivity: Due to its high proportion of overseas assets, its earnings are more susceptible to global interest rate fluctuations (e.g., US Federal Reserve policy) than its domestic-focused peers.

Opportunities

- RMB Internationalization: As more trade is settled in RMB (driven by “Belt and Road” initiatives), BOC is positioned to capture the lion’s share of transaction fees.

- Digital Transformation: The bank is heavily investing in AI-driven wealth management platforms to compete for tech-savvy younger clients by 2026.

Threats

- Geopolitical Risks: High overseas exposure makes the bank vulnerable to international regulatory changes, sanctions, and currency volatility.

- Retail Competition: Joint-stock banks like China Merchants Bank are highly aggressive in private banking and high-end retail, eroding BOC’s traditional advantages in wealth management.

3. Primary Competitors (2025-2026 Dynamics)

- China Merchants Bank (CMB): Known as the “Retail King,” CMB poses the biggest threat in terms of Return on Equity (ROE) and customer loyalty. In 2025, CMB’s Tier 1 Capital ranking rose to 8th globally, directly challenging BOC’s commercial dominance.

- Global Giants (HSBC, Citi): In the realm of trade finance, BOC competes head-to-head with HSBC in the Asia-Pacific region. BOC has been closing the gap by winning “Best Overseas Service Bank” awards in 2025, aiming to capture more multinational corporate accounts.

In the global arena, Bank of China (BOC) faces intense competition from world-class financial institutions such as HSBC, Citigroup, and Standard Chartered. Unlike its domestic peers, BOC’s strategy is deeply intertwined with global trade flows and the internationalization of the Renminbi (RMB).

Based on 2025-2026 market dynamics, here is a detailed analysis of BOC versus its primary international rivals:

1. Key Performance Indicators (2025–2026 Estimates)

| Feature | Bank of China (BOC) | HSBC | Citigroup (Citi) | Standard Chartered |

| Global Rank (Assets) | 4th | 7th | 12th | Top 30 |

| Dominant Market | China & Global RMB | Asia & Europe | North America & Global | Asia, Africa & Middle East |

| Trade Finance Focus | RMB-denominated Trade | Multi-currency Supply Chain | Institutional Custody | Emerging Markets / Belt & Road |

| Digital Strategy | BOC Pay / Cloud Banking | “Global Money” App | Tokenized Assets (Solana) | Digital Bank (Mox) |

| Key Competitive Edge | CIPS/RMB Monopoly | Network Breadth | Institutional Services | Local Emerging Market Roots |

2. Strategic Competitive Dynamics

The Battle for Trade Finance

- BOC’s Dominance: BOC currently holds the highest market share in RMB cross-border settlement. As of late 2025, RMB trade settlement reached a record 12.7 trillion RMB, giving BOC a significant cost and pricing advantage for any trade involving China.

- HSBC’s Challenge: HSBC remains the world’s leading trade finance bank by volume. In 2025, HSBC’s competitive edge lies in its blockchain-based supply chain finance, which is currently perceived to have a 1-2 year lead in technological integration over BOC’s internal systems.

Institutional & Custody Services

- Market Share: As of 2026, the global institutional custody market is projected to reach 32.7 billion USD. Citigroup and HSBC are the primary incumbents.

- BOC’s Entry: BOC has aggressively expanded its custody services for international institutional investors entering China’s bond and equity markets. While Citi leads in multi-asset complexity, BOC is the “go-to” for domestic regulatory compliance.

The “China+1” Supply Chain Shift

- Standard Chartered’s Advantage: As manufacturing shifts to Southeast Asia and India, Standard Chartered has utilized its decades-long local presence to capture new financing demands.

- BOC’s Counter: BOC has countered this by significantly increasing its “Belt and Road” credit lines, leveraging state-backed projects to secure its position in these emerging trade corridors.

3. Comparative SWOT (International Perspective)

Strengths

- RMB Gatekeeper: BOC is the primary clearing bank for RMB in major global hubs (London, New York, Singapore).

- State Support: In volatile geopolitical climates, BOC offers a level of stability for large-scale state-owned enterprise (SOE) investments that foreign banks cannot match.

Weaknesses

- Brand Perception: In non-China-related corridors (e.g., Brazil-USA trade), BOC lacks the brand legacy of Citi or HSBC.

- Compliance Costs: BOC has seen a sharp rise in anti-money laundering (AML) and data-sharing compliance costs as it navigates divergent regulations between the East and West.

Opportunities

- Real-World Asset (RWA) Tokenization: With new 2026 PBOC guidelines defining RWA, BOC has a massive opportunity to lead in licensed on-chain financial infrastructure, rivaling Citi’s recent Solana-based tokenization projects.

- The “Greater Bay Area” (GBA): The Wealth Management Connect 2.0 initiative gives BOC a natural home-field advantage in capturing high-net-worth flows between HK and mainland China.

Sources:

- Bank of China Official Website: https://www.boc.cn/en/aboutbi/bi1/

- Wikipedia – Bank of China: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bank_of_China

- 21st Century Business Herald – 2025 China Banking Competitiveness Rankings: https://www.21jingji.com/article/20251122/herald/a2857faf4c1158853f2c4939b363101f.html

- KPMG – China Banking Outlook 2026: https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmgsites/cn/pdf/zh/2025/12/china-banking-outlook-2026.pdf

- Global Finance – Stars of China 2025: https://gfmag.com/award/stars-of-china-2025/

- AASTOCKS Financial News (Feb 2026): http://www.aastocks.com/en/stocks/news/aafn-con/NOW.1502316/positive-news/AAFN

- Fortune Business Insights – Trade Finance Market 2034: https://www.fortunebusinessinsights.com/trade-finance-market-111943

- HSBC Market Outlook 2026: https://www.hsbc.com.tw/en-tw/wealth/insights/market-outlook/china-in-focus/five-key-china-macro-themes-for-2026/

Back to Bank of China page