The history of Coca Cola is a classic tale of American entrepreneurship, evolving from a local tonic into a global cultural icon. Here is the chronological breakdown of its evolution:

1. Invention and Early Foundations (1886–1891)

In 1886, Dr. John Pemberton, an Atlanta pharmacist, created a distinctive tasting soft drink as a non-alcoholic version of coca wine. His bookkeeper, Frank Robinson, named the product “Coca-Cola” and designed the flowing script logo that is still used today. Initially sold at soda fountains as a medicinal tonic for 5 cents a glass, the brand’s potential was realized by businessman Asa Candler, who purchased the formula and patents by 1891 for approximately $2,300.

Major Acquisitions or Partnerships: Between 1888 and 1891, businessman Asa Candler recognized the potential of pharmacist John Pemberton’s formula and acquired the trademarks, formulas, and patents in stages for a total of approximately $2,300. This acquisition transformed a local tonic into a commercial enterprise.

Revenue Level: During this nascent stage, scale was minimal; in 1886, the company averaged only 9 servings per day, with negligible annual revenue.

2. Expansion and the Birth of the Contour Bottle (1892–1922)

Asa Candler incorporated The Coca-Cola Company in 1892. He used aggressive marketing, such as distributing coupons for free glasses of Coke, to drive demand. In 1899, the first bottling rights were sold for just $1, creating a unique franchising model where the company sold syrup to independent bottlers. To combat “copycat” brands, the iconic Contour Bottle was introduced in 1915, designed to be recognizable even if felt in the dark or broken on the ground.

Major Acquisitions or Partnerships: In 1899, the famous “1 Dollar Bottling Contract” was signed, selling the rights to bottle and distribute the drink across most of the U.S. to independent partners. This established the high-margin model of selling syrup while outsourcing production. In 1906, a 50-year strategic partnership with the D’Arcy Advertising Company began, launching large-scale modern marketing.

Revenue Level: With the expansion of the bottling network, annual revenue first surpassed $1 million in the early 1900s. By 1919, when the company was sold to a group of investors, the acquisition price had surged to $25 million.

3. The Woodruff Era and Global Dominance (1923–1959)

Robert Woodruff became president in 1923 and spent 60 years leading the company’s expansion. He introduced the “six-pack” carrier to encourage home consumption. During World War II, Woodruff vowed that every American soldier would be able to buy a Coke for 5 cents, regardless of where they were stationed. This led to the establishment of dozens of bottling plants overseas, effectively introducing the drink to the world and cementing it as a symbol of American freedom.

Major Acquisitions or Partnerships: During WWII, a unique supply partnership was formed with the U.S. government to establish 64 overseas military bottling plants. In 1946, the company officially acquired the rights to the Fanta brand (originally developed in Germany). In 1955, an exclusive supplier partnership was established with McDonald’s, a relationship that remains one of the most successful in business history.

Revenue Level: Revenue was approximately $31 million in 1920. By the late 1950s, driven by post-war globalization, international markets contributed over 30% of total revenue.

4. Product Diversification and the New Coke Crisis (1960–1989)

The company began expanding its portfolio, launching Sprite in 1961, TAB in 1963, and Diet Coke in 1982. In 1985, facing stiff competition from Pepsi, the company famously changed its secret formula to launch “New Coke.” The backlash was immediate and intense, with thousands of angry letters and phone calls. After only 79 days, the company returned the original formula to the market as “Coca-Cola Classic,” which actually resulted in a massive surge in brand loyalty.

Major Acquisitions or Partnerships: The company acquired Minute Maid in 1960, marking its entry into the juice market. In 1982, it made a major cross-industry acquisition of Columbia Pictures for $692 million (later sold to Sony in 1989 for $3 billion). In 1986, it formed and took public Coca-Cola Enterprises (CCE) to consolidate major North American bottling operations.

Revenue Level: By 1985, revenue grew to approximately $7.36 billion. This era focused on multi-brand acquisitions to diversify risks away from a single carbonated soft drink.

5. Transition to a Total Beverage Company (1990–Present)

Under modern leadership, Coca-Cola has shifted from being a “soda company” to a “total beverage company.” This era is defined by massive acquisitions, including Minute Maid, Innocent smoothies, and Costa Coffee. Today, the strategy focuses on reducing sugar across its portfolio, investing in sustainable packaging, and utilizing digital marketing to reach Gen Z through global platforms and the “Real Magic” brand philosophy.

Major Acquisitions or Partnerships: The company pursued aggressive global acquisitions, including Thums Up in India (1993), Costa Coffee (2018, $5.1 billion), and Bodyarmor (2021, $5.6 billion). Simultaneously, it executed a “Re-franchising” strategy, selling low-margin bottling assets back to local partners to focus on brand management and syrup production.

Revenue Level: Revenue peaked at $48 billion in 2012. By 2024, revenue stood at approximately $47.06 billion. While top-line figures fluctuated due to the divestment of bottling assets, operating margins significantly improved to over 30%.

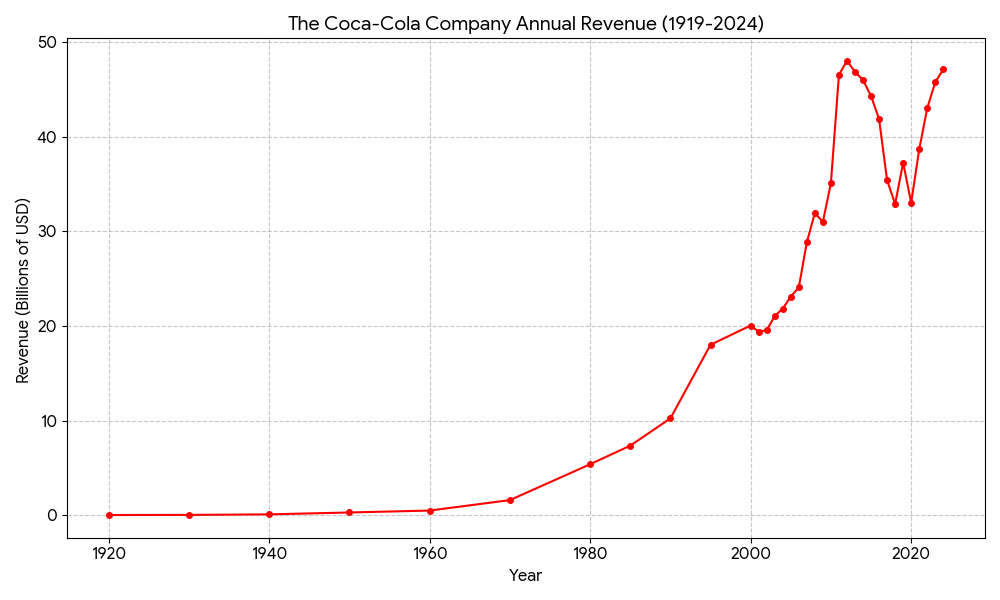

Coca-Cola Annual Revenue Trends (1919-2024)

This chart illustrates the company’s financial growth over more than a century. Several key inflection points are reflected in the data:

- Early Steady Growth (1920s-1970s): During this period, Coca-Cola evolved from a local enterprise with approximately $32 million in revenue to a multinational corporation surpassing $1.6 billion in annual sales.

- Rapid Expansion Era (1980s-2012): Driven by global expansion and strategic brand acquisitions, revenue reached a historical peak of $48.01 billion in 2012.

- Strategic Transformation (2012-2018): You may notice a significant dip in revenue during this time. This was not a decline in brand strength but a result of the “Re-franchising” strategy. The company sold off its lower-margin bottling operations to local partners to pivot toward a high-margin model focused on syrup production and brand management.

- Post-Pandemic Recovery (2019-2024): Following its successful transition into a “Total Beverage Company,” revenue rebounded to approximately $47.1 billion by 2024, with a much more resilient and profitable cost structure.

A competitive analysis of The Coca-Cola Company reveals a landscape where the primary battle has shifted from “Colas” to “Total Beverages.” Here is the breakdown:

1. Direct Rivalry: Coca-Cola vs. PepsiCo

This is the most iconic rivalry in business history, but the two companies have diverged in strategy:

- Diversification Strategy:

- Coca-Cola is a pure-play beverage company. It focuses on drinking occasions across all categories (sparkling, water, juice, coffee).

- PepsiCo is a diversified food and beverage giant. About 55% of its revenue comes from snacks and convenient foods (Frito-Lay, Quaker).

- Operating Margins: Coca-Cola generally maintains higher operating margins (often 28-30%+) compared to PepsiCo (around 13-15%) because Coca-Cola’s “asset-light” model focuses on selling high-margin concentrates while PepsiCo manages more of its own distribution and manufacturing.

- Channel Dominance: Coca-Cola holds a significant advantage in the “Away-from-Home” channel (fountain drinks in restaurants like McDonald’s and Subway).

2. Competitive Landscape: Strategic Categories

Coca-Cola faces competition beyond just Pepsi; it competes across several beverage “need states”:

- Energy & Sports: Competes with Monster Energy (Coke owns a minority stake), Red Bull, and Gatorade (PepsiCo).

- Coffee & Tea: Competes with Starbucks (RTD products) and Nestlé (Nespresso/Nescafé) following the acquisition of Costa Coffee.

- Hydration: Competes against Nestlé Waters and various premium brands like Fiji or Voss.

- Disruptive Challengers: New, health-focused brands like Celsius (energy) or Olipop (prebiotic soda) are challenging traditional soda dominance among Gen Z.

3. Porter’s Five Forces Analysis

- Threat of New Entrants: Low. While anyone can make a soda, the barrier to entry is the distribution network. Replicating Coca-Cola’s global “last mile” reach is nearly impossible for new players.

- Bargaining Power of Buyers: Moderate to High. Large retailers like Walmart and Costco have high bargaining power. Individual consumers have low power but can easily switch to a competitor if prices rise too sharply.

- Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Very Low. Coca-Cola’s massive scale allows it to dictate terms to suppliers of sugar, aluminum, and packaging.

- Threat of Substitutes: Very High. Consumers can choose water, tea, coffee, or juice. This is the biggest threat to the core sparkling business.

- Intensity of Rivalry: Very High. The market is mature, meaning growth often comes from taking market share from rivals through aggressive marketing and pricing.

4. Competitive Advantages (The “Moat”)

- Intangible Assets: The Coca-Cola brand is valued at nearly $100 billion. This brand equity allows for pricing power, enabling the company to raise prices during inflationary periods without losing significant volume.

- Distribution Scale: Their system reaches over 200 countries. If a new beverage trend emerges, Coke can plug a new product into this “global machine” faster than any competitor.

- Marketing Budget: With an annual advertising spend exceeding $4 billion, they maintain “top-of-mind” awareness that smaller rivals cannot match.

The competition between Coca-Cola and PepsiCo, famously known as the “Cola Wars,” is one of the longest-running and most influential rivalries in business history. It has shaped modern marketing, distribution strategies, and global pop culture.

1. Early Confrontation and the Value War (1890s – 1930s)

In the early 20th century, Coca-Cola was the undisputed market leader, while PepsiCo struggled, even facing bankruptcy multiple times.

- The Price Strategy: During the Great Depression, Pepsi launched a brilliant campaign offering a 12-ounce bottle for 5 cents, while Coke offered only 6.5 ounces for 5 cents. This “twice as much for a nickel” strategy allowed Pepsi to survive and establish itself as a high-value alternative.

- Identity Positioning: Coca-Cola positioned itself as the “original,” traditional, and wholesome American drink, while Pepsi began targeting value-conscious consumers.

2. The Peak of the “Cola Wars” (1970s – 1980s)

This era saw the most aggressive marketing tactics as Pepsi attempted to dethrone the king.

- The Pepsi Challenge (1975): Pepsi launched a nationwide blind taste test campaign. When results showed that consumers preferred the sweeter taste of Pepsi over Coke, it shook Coca-Cola’s leadership confidence.

- The “New Coke” Crisis (1985): In a panicked response to the Pepsi Challenge, Coca-Cola changed its 99-year-old formula. The backlash from loyalists was so severe that the company had to bring back the original formula as “Coca-Cola Classic” just 79 days later. Paradoxically, this mistake reinforced the emotional bond consumers had with the original brand.

- Celebrity Endorsements: Pepsi aggressively courted the younger generation by signing icons like Michael Jackson, positioning itself as “The Choice of a New Generation,” while Coke focused on global unity themes, such as the famous “I’d Like to Buy the World a Coke” ad.

3. Strategic Divergence (1990s – 2010s)

The two giants began to follow very different paths to growth:

- PepsiCo: The Diversification Path: Under leaders like Roger Enrico and Indra Nooyi, Pepsi shifted focus toward snacks and nutrition. By acquiring Frito-Lay and Quaker Oats, Pepsi became a food-and-beverage powerhouse, insulating itself from the decline in soda consumption.

- Coca-Cola: The Beverage Specialist: Coke remained a “pure-play” beverage company. It doubled down on its Total Beverage strategy, acquiring Minute Maid, Glacéau (Vitaminwater), and Costa Coffee, while selling off its bottling plants to focus on high-margin syrup sales.

4. The Modern Rivalry: Health and Sustainability (2020s – Present)

Today, the battle is less about sugar and more about functional benefits and ESG:

- The Battle of “Zero”: Both companies are heavily investing in Zero Sugar formulations that mimic the original taste as closely as possible to retain health-conscious consumers.

- Asset-Light vs. Integrated: Coca-Cola’s model is “asset-light,” resulting in higher profit margins (approx. 30%+). PepsiCo’s model is vertically integrated with a massive logistics footprint for its snacks, resulting in higher total revenue but lower margins.

- The “Last Mile” Advantage: Coca-Cola maintains a dominant lead in the “Away-from-Home” segment, securing exclusive multi-year contracts with major fast-food chains like McDonald’s, while Pepsi partners with chains like Taco Bell and KFC (formerly owned by PepsiCo).

Source:

- Coca-Cola History | The Coca-Cola Company

- Coca-Cola (KO) Revenue History | Macrotrends

- The Pepsi Challenge: How a Taste Test Changed Marketing | Investopedia

- Coca-Cola’s Re-franchising Strategy | Business Insider

- Coca-Cola vs. PepsiCo: Competitive Analysis | Forbes

- The Story of New Coke | Britannica

- Coca-Cola and McDonald’s: A Success Story | New York Times

Back to Coca Cola page